Women often find themselves filling roles they never asked to be in. Yxta Maya Murray captures the roles that Latina women find themselves in. Murray’s novel Locas is based around the lives of two young women, Lucia and Cecilia, as they attempt to escape the roles that have been forced upon them by their gender.

Amaia Ibarraran Bigalondo, in her article entitled “Chicano Gangs/Chicanca Girls: Surviving the ‘Wild Barrio’” describes gender roles in Chicana culture. She states that “In such a highly hierarchical and male dominated social microstructure, the role of women is the traditional one, perpetrated down through generations and reinforced by popular culture in general.” (Bigalondo 49).

Bigalondo is saying that the gender roles these women face are passed down from several generations before them, and are engrained in their culture. This makes these norms and stereotypical roles more difficult for the newest generation to escape. Cecilia and Lucia are both women of the generation that is currently in power during the time of the novel (late 1980’s/early 1990’s). They both shatter gender norms in their own way.

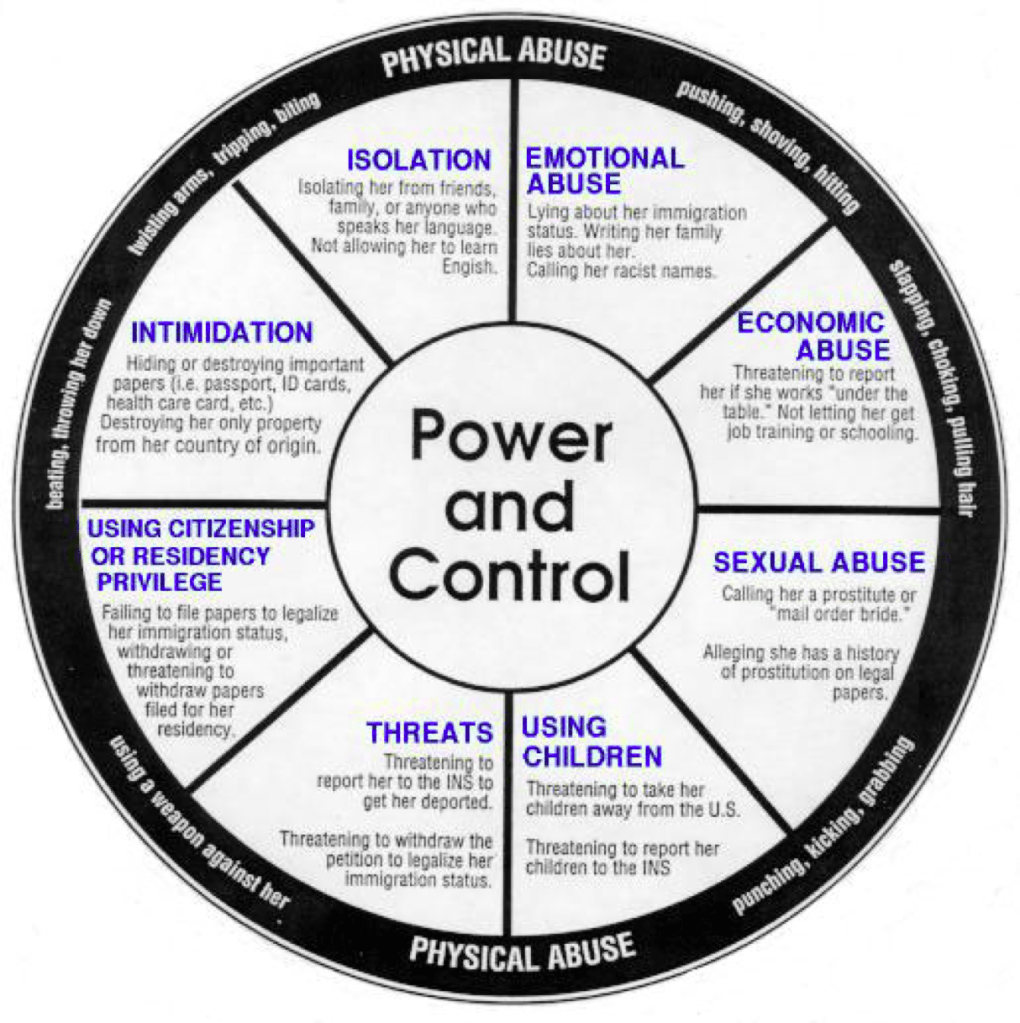

Lucia finds herself confined to the role of a “sheep”. This role is forced upon her because she is a woman and she is in a relationship with Manny. Women in the novel who are in relationships with gang members are referred to as “sheep” because they are expected to follow the man they are attached to, do what he says, and never talk back.

Lucia flips this gender role on its backside as she uses the men in her life to her advantage. She seduces Beto and convinces him to challenge Manny as the leader of the Lobos, effectively getting Manny out of the way. It is at this time that she is able to start exercising her control as the real leader of the Lobos, making Beto the figurehead while she holds the real power.

Lucia also goes on to start her own gang of women which she calls her “fire girls”. This itself is breaking gender barriers. BIgalondo makes the point that Lucia’s female gang, though fictional in the novel, is relevant to current gang life. She states “The number of female gangs is fast increasing, as is the involvement of girls in gangs, providing a ‘way out’ from ‘poverty, illness, and despair.’”(Bigalondo 49).

Bigalondo is arguing that this system that has been passed down through several generations of Chicana gangs is no longer working, and that women are making societal and cultural changes to their advantage. This is exactly what Lucia does when forming her gang of “Fire Girls”.

Cecilia also breaks several gender barriers during the Murray’s novel. Cecilia enters into a relationship that breaks two gang norms. Her relationship with Chucha is barrier breaking because it is a relationship between two women, and because Cecilia is a Lobo and Chucha is a C-4. An inter-gang, homosexual relationship removes Cecilia from her role as a sheep entirely.

Cecilia eventually removes herself from gang life entirely and becomes a religious cleaning woman. She is driven by a desire to liberate herself from her sins during her time as a member of the Lobos and the hell she lived through during that time. Bigalondo states that “Cecilia, after a miscarriage and falling in love with another woman, consciously retired from gang and even public life and seeks shelter and comfort in totally devoted service to the Catholic Church.” (Bigalondo 50). Bigalondo is attempting to explain Cecilia’s way of shattering the expected role that was forced upon her.

Cecilia and Lucia both escape their fate as Chicana women in gang life of becoming a sheep by shattering gender norms and expectations. Cecilia turns to liberation through religion, and Lucia exercises control over the Lobos as well as her Fire Girls.

Works Cited

Bigalondo, Amaia I. “”Chicano Gangs/Chicana Girls: Surviving the ‘Wild Barrio'”.” pp. 49-50.

Murray, Yxta M. Locas. New York City, Grove Press, 1997.